Branching

Cue:

A linear history is fine, but that is often not how science progresses.

Suppose that you've got your project working, but want to get tidy it up a bit in a way that requires major surgery and you want to be able to get back to where you were.

Alternatively, suppose that you want to try two different ways of implementing something.

In my case, I have a package that I mantain -- sometimes I need to add bug fixes to the released version without wanting to publish the broken development code.

What if you wanted to go back to an old version and continue development from there?

In all of these scenarios, we might want to work on a "branch" of the project.

What do branches look like?

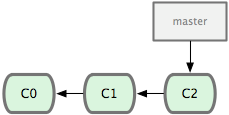

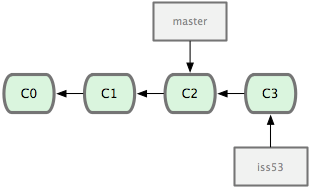

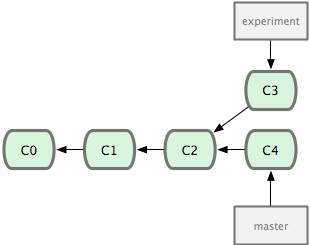

Suppose that we have a repository with three commits: C0, C1 and C2:

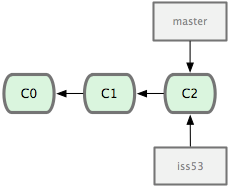

at the moment there is only one branch: "master". Now imagine that

we're going to do some work starting at this point -- we'll create a

new branch that starts from our current point (C2), in this case

called iss53 (the diagrams come from the excellent

Pro Git book, and I've not redrawn them --

for an ecologist this might be "experiment" or "reorganise_data").

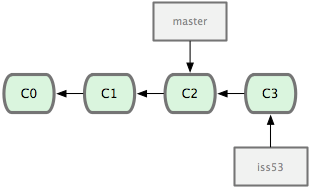

We then continue to do work on this new branch:

At this point, we might be happy with the new work and just want to

merge the branches back together (moving the master pointer up to

C3).

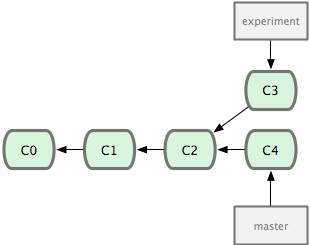

Alternatively, you might have to do some work on master (perhaps

your supervisor needs you to tweak a figure for a talk they are giving

right now, but your current state on iss53 would break it). You

could then switch back to branch master and do some more work there

too:

(Note that the iss53 branch has been renamed experiment here!)

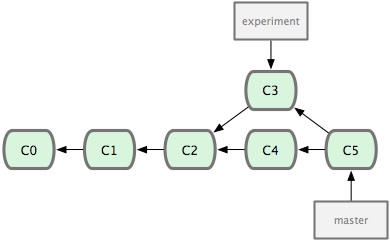

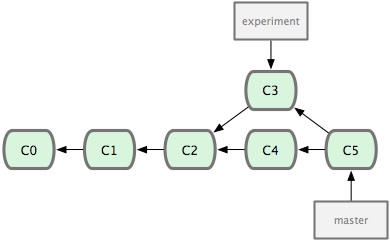

Now you your history has diverged -- both commits C3 and C4 have

C2 as a parent, but they consist of different work. You have a

choice of how you want to resolve the diverge this to get the work

done on C3 and C4 onto the same branch. First you can merge

the changes together:

this means that C5 has two parents (C3 and C4) and that it

includes the content of both.

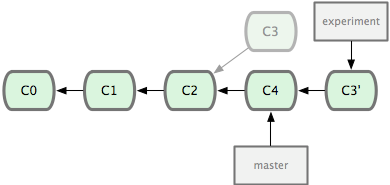

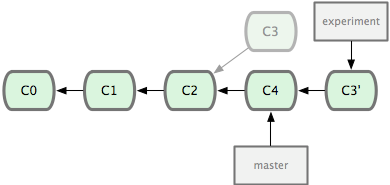

Alternatively there is a strategy called rebase where we would

replay the changes on the experiment branch on the master branch,

which gives a linear history:

What this does is to look at the difference between C3 and C2, and

then apply that difference to C4 so that the new commit C3'

contains the results of C4 and C3. The old C3 commit is then

dropped.

Note that the contents of C3' and C5 will likely be the same

at the end of these two operations -- the difference is in the

interpretation of how they came into being.

Workflows that use branches

Branches most naturally appear in a project that is simultaneously being worked on by different people. It turns out the git will see branches in someone else's repository essentially like branches in your own, and lots of cool ways of working with branches become possible.

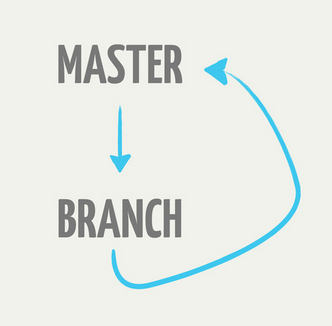

They also are important for single-user workflows. I use them for testing ideas that I'm not sure about:

- Create a branch

- Commit a bunch of work to it

- Decide if I like the work and if so...

- Merge it back into the main branch

This idea is nicely formalised in this flow chart.

Much more complicated (but powerful in the right hands) workflows are possible, such as the so-called git-flow workflow.

Listing branches

The command git branch lists the branches git knows about. By

default, there is only one branch and it is called master.

git branch

* master

The asterisk next to this indicates that this is the current branch.

If you pass in the -v argument (for verbose), you get

git branch -v

* master a0f9f69 Added RStudio files

which adds the shortened version of the SHA hash and the last commit message.

Creating branches

There are two ways of creating branches in git. The first is to use

git branch. The command

git branch new_idea

creates a new branch called new_idea, but does not change to it.

Rerunning git branch -v:

* master a0f9f69 Added RStudio files

new_idea a0f9f69 Added RStudio files

We now have two branches, both at the same point on the tree. The

asterisk indicates that we are on the branch master.

You can change to a branch by using git checkout. So to switch to

the new_idea branch, you would do:

git checkout new_idea

which lets you know that it worked

Switched to branch 'new_idea'

You can switch back to master by doing

git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

and can delete branches by passing -d to git branch

git branch -d new_idea

which prints

Deleted branch new_idea (was a0f9f69).

The other way of creating a branch and switching to it is to pass -b

as an argument to checkout:

git checkout -b new_idea

Switched to a new branch 'new_idea'

Now git branch shows:

master

* new_idea

as we both created and switched to the new branch new_idea.

How branches grow

New work is commited to the current active branch (the one with the

asterisk next to it in git branch (at the moment this is the branch

new_idea. So if we edit a file and do git commit.

# ...edit file...

git add script.R

git commit -m "Modified function to make NA treatment optional"

The history is now equivalent to this picture from before:

You can also see a picture of this with some arguments to git log:

git log --graph --decorate --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit

* 37485b1 (HEAD, new_idea) Modified function to make NA treatment optional

* a0f9f69 (master) Added RStudio files

* 9b5f828 Added function that computes standard error of the mean

(which will even be in colour if you set that up)

Merging branches back together

Suppose that you are happy with the changes that you made and want to

merge them into your master branch.

To do the merge, you first check the master branch back out:

git checkout master

which will output

Switched to branch 'master'

then

git merge new_idea

which will output

Updating a0f9f69..37485b1

Fast-forward

script.R | 3 +-

1 file changed, 3 insertions(+), 2 deletions(-)

telling you that master was "fast-forwarded" from a0f9f69 to

37485b1, changing one file (script.R) by inserting three lines and

deleting two.

The tree now has two branches that "point" at the last commit:

master and new_idea. We can delete the new_idea branch with

git branch -d new_idea

(the -d argument stands for delete).

Merging when branches have diverged

If you have a history like this one:

as noted above you have two choices -- you can merge or you can

rebase. Suppose for now that we have checked out experiment.

You would switch to to branch master by running

git checkout master

and then merge the experiment in with

git merge experiment

which gives a history like this:

The alternative would be to run

git checkout master

git rebase experiment

which results in a history like this:

In both cases, you could delete the experiment branch with

git branch -d experiment

What you chose is often mostly a matter of taste (and there are a diversity of opinions on this). For a single-user workflow it often does not make much difference.

Sometimes, the change on a branch all falls in a logical chunk, and it

might make good sense to merge that in with merge to reflect this in

your history. Other times, the different branches just reflect

working on different computers, or changes that make sense when

reordered linearly. In that case, rebase is often the best bet.

Branches and old versions

Suppose that you want to look an old version (say, C2 in the graphs

above). You can simply do to

git checkout C2

which will produce the rather scary message:

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by performing another checkout.

If you want to create a new branch to retain commits you create, you may

do so (now or later) by using -b with the checkout command again. Example:

git checkout -b new_branch_name

HEAD is now at 5d522e6... Added RStudio files

What this means: - you can't commit anything - any changes you make will be lost when you go back to a "proper" branch.

If you did want to start a branch here, you can do

git checkout -b revisit_old_analysis

which will start a new branch at the point C2. You can then

continue adding to that branch with git commit, or just easily

switch back to it.

You could also have done both things in one step, from master:

git checkout -b revisit_old_analysis C2

which would start a new branch called revisit_old_analysis at the

point in history C2.

Concluding remarks

Branching is git's "killer feature" -- the thing that it does better than most other version control systems. Branches are addictive, and once you get used to using them, you'll find all sorts of use for them. Branches are very fast to create, to switch between, and to destroy. If they help you structure your work, you should use them!

There is an incredible Git branching demo that is useful to work through learning about git branches. It also has a tutorial mode with lots of lessons.